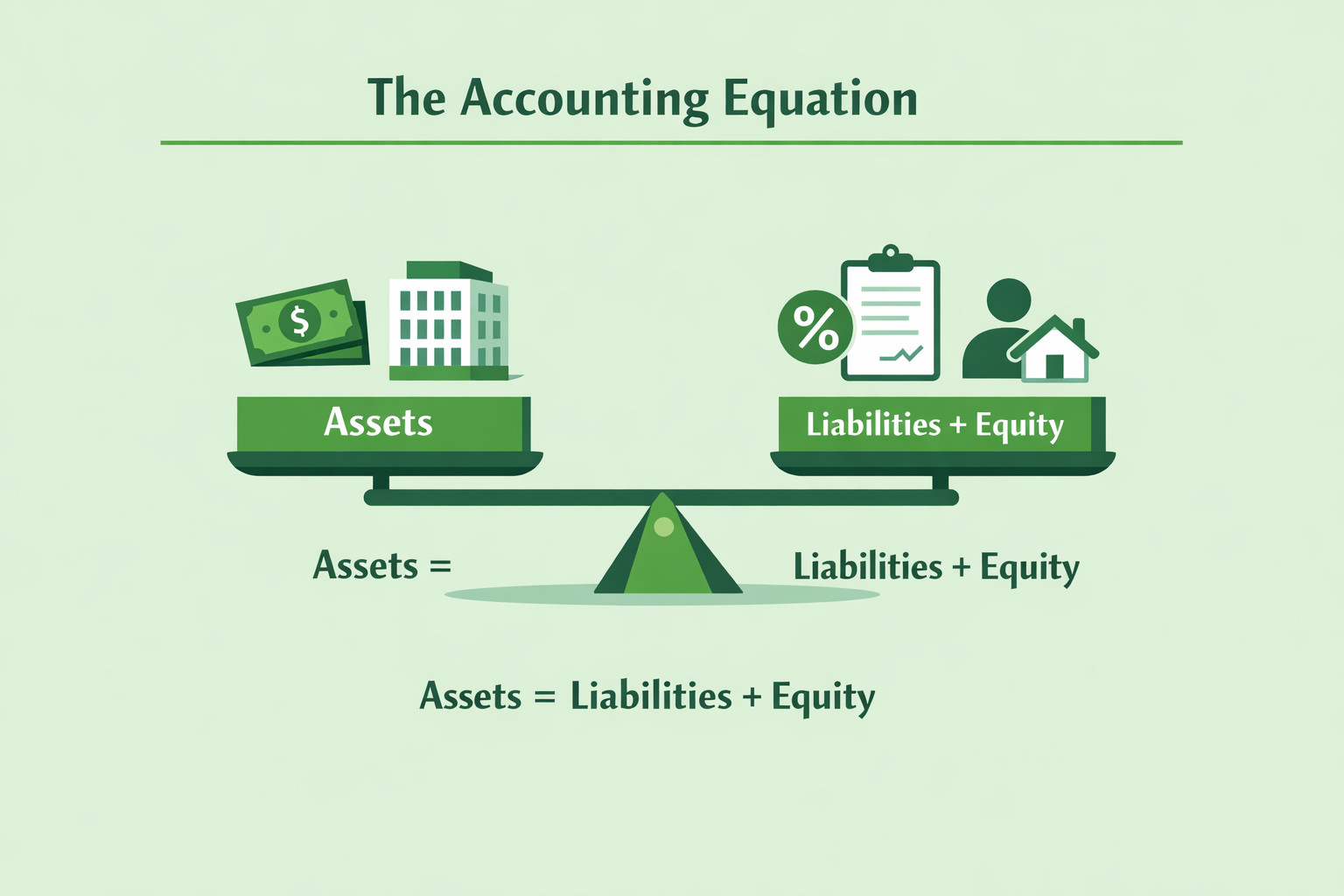

At the heart of accounting lies one simple but powerful concept: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. This equation forms the foundation of all modern accounting systems, from small businesses keeping basic records to multinational corporations producing complex financial statements. While it may look like a simple formula, the accounting equation represents the complete financial structure of a business and explains how resources are funded and owned.

For business owners and non-accountants, the accounting equation provides a clear framework for understanding financial health. It answers fundamental questions such as where the company’s resources come from, how much is owed to others, and how much truly belongs to the owners. Every transaction a business makes—whether it involves buying equipment, taking a loan, earning revenue, or paying expenses—affects this equation in some way.

Understanding this equation is not just an academic exercise. It is essential for interpreting balance sheets, making informed decisions, and ensuring accurate financial records. Without grasping the accounting equation, financial statements can feel confusing or meaningless. With it, accounting becomes logical, structured, and much easier to understand. This article explains the accounting equation in detail, breaks down each component, and shows why it matters for everyday business operations.

Understanding Assets

Assets are the economic resources a business owns or controls that are expected to provide future benefits. In simple terms, assets are everything a business uses to operate and generate income. Common examples include cash, inventory, equipment, buildings, vehicles, and accounts receivable. Assets can also be intangible, such as trademarks, software, or goodwill.

Assets are usually classified into current assets and non-current assets. Current assets are expected to be used or converted into cash within one year, such as cash, inventory, and receivables. Non-current assets are long-term resources, such as property, machinery, or long-term investments. This classification helps users of financial statements understand liquidity and long-term stability.

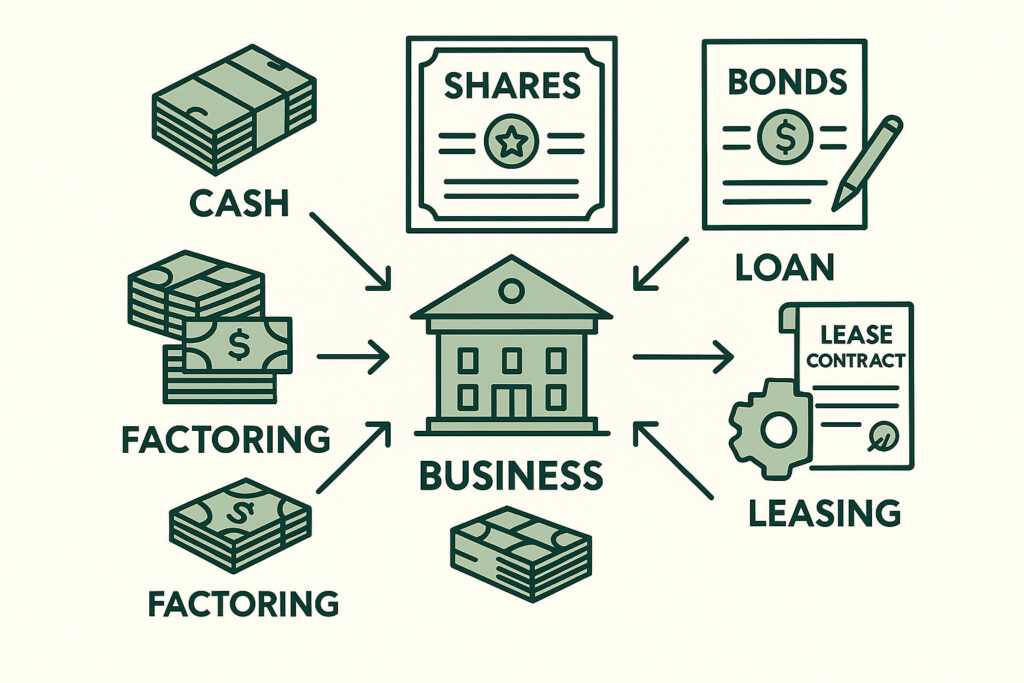

From the accounting equation perspective, assets represent the left side of the equation and show what the business has at its disposal. However, assets do not exist on their own. Every asset must be financed either through borrowing (liabilities) or through owner investment and retained profits (equity). This is why assets are always equal to liabilities plus equity.

Understanding assets helps business owners evaluate operational capacity, efficiency, and growth potential. A company with strong assets but weak cash flow, for example, may struggle to meet short-term obligations. Therefore, assets are not just about size, but about quality, liquidity, and usefulness in achieving business goals.

Understanding Liabilities

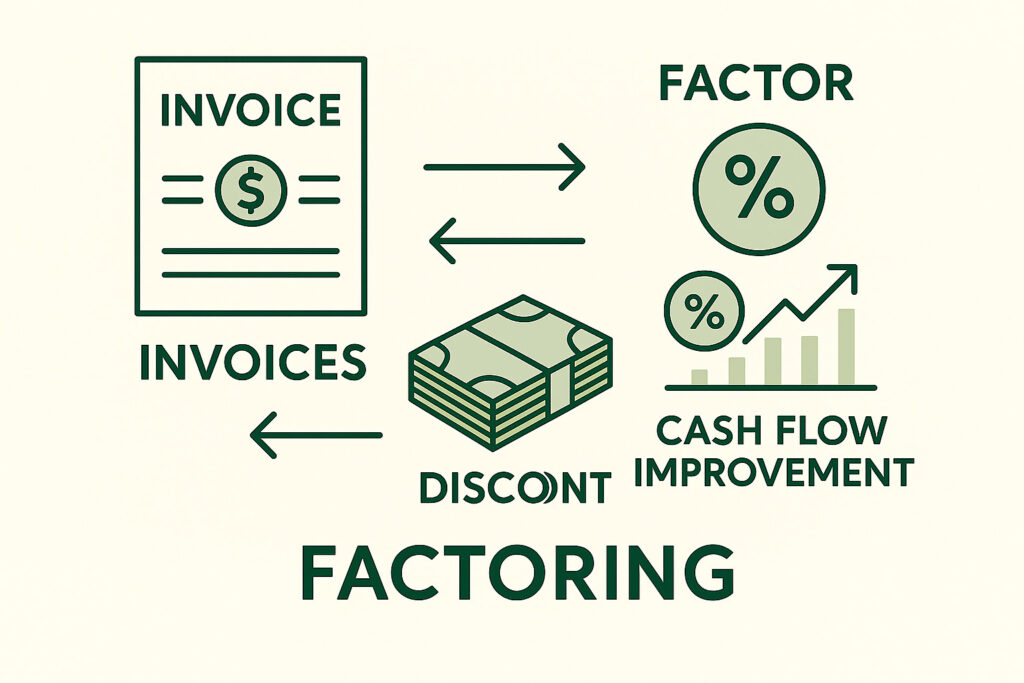

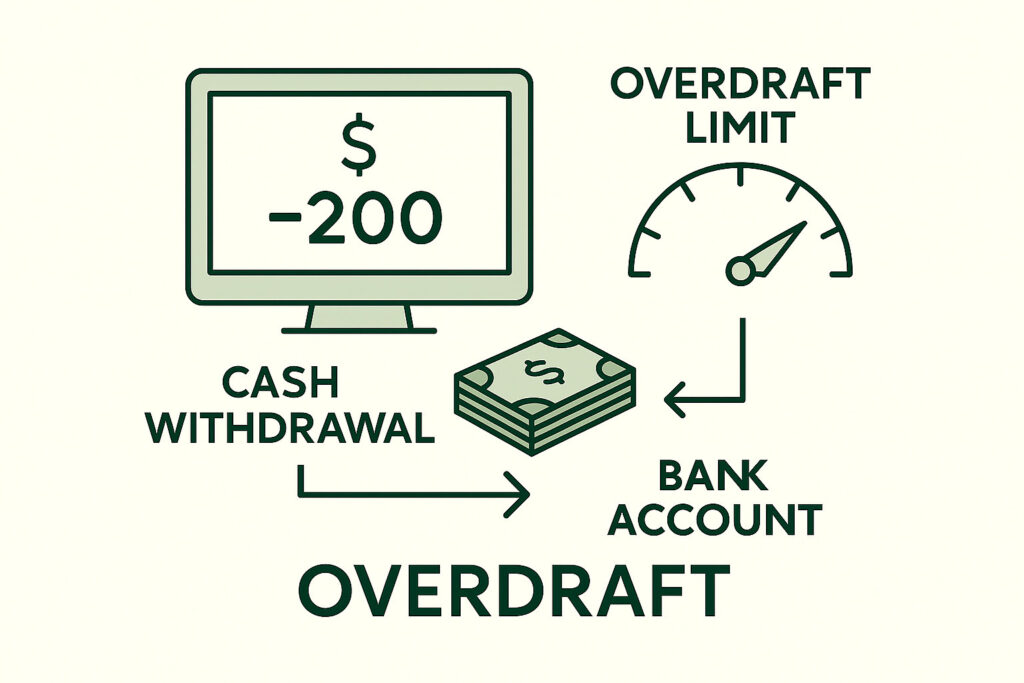

Liabilities represent the obligations or debts a business owes to external parties. These can include loans, accounts payable, taxes payable, overdrafts, and accrued expenses. Essentially, liabilities are claims on the business’s assets by creditors, suppliers, banks, and other third parties.

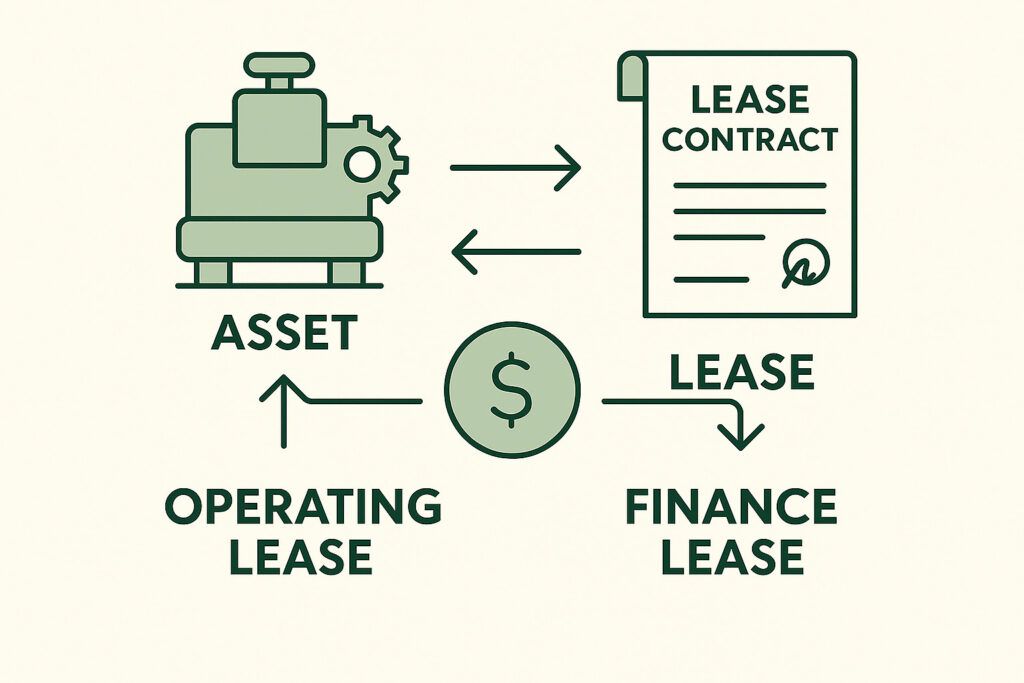

Like assets, liabilities are classified into current liabilities and non-current liabilities. Current liabilities are obligations due within one year, such as supplier invoices, short-term loans, and tax liabilities. Non-current liabilities are long-term obligations, including bank loans, bonds, and lease liabilities. This classification helps assess the company’s short-term liquidity and long-term financial commitments.

Within the accounting equation, liabilities explain where part of the assets came from. If a company buys equipment using a bank loan, the equipment becomes an asset, while the loan becomes a liability. The equation remains balanced because both sides increase by the same amount. This illustrates a key accounting principle: every transaction has at least two effects.

For business owners, understanding liabilities is crucial for managing financial risk. Excessive liabilities can strain cash flow and limit future borrowing capacity. However, liabilities are not inherently bad. When managed responsibly, they can help businesses grow, expand operations, and improve returns. The key is understanding how liabilities fit into the overall financial structure and ensuring they remain sustainable.

Understanding Equity

Equity represents the owner’s residual interest in the business after liabilities are deducted from assets. In simple terms, equity is what belongs to the owners if all assets were sold and all liabilities were paid off. Equity includes owner contributions, share capital, retained earnings, and reserves.

Equity increases when owners invest additional funds or when the business earns profits. It decreases when owners withdraw money or when the business incurs losses. Unlike liabilities, equity does not represent an obligation to repay external parties. Instead, it reflects ownership and long-term commitment to the business.

In the accounting equation, equity explains the internal source of funding for assets. While liabilities represent borrowed funds, equity represents owner-funded resources. Together, liabilities and equity show how all assets are financed. This makes equity a critical measure of financial stability and long-term sustainability.

For business owners, equity provides insight into value creation. Growing equity over time usually indicates a profitable and well-managed business. Investors and lenders closely examine equity levels to assess risk and financial strength. A business with strong equity is generally more resilient during economic downturns and better positioned for growth.

Understanding equity helps business owners see beyond short-term performance and focus on long-term value. It connects daily operations, profitability, and strategic decisions to the overall financial health of the business.

How the Accounting Equation Works in Practice

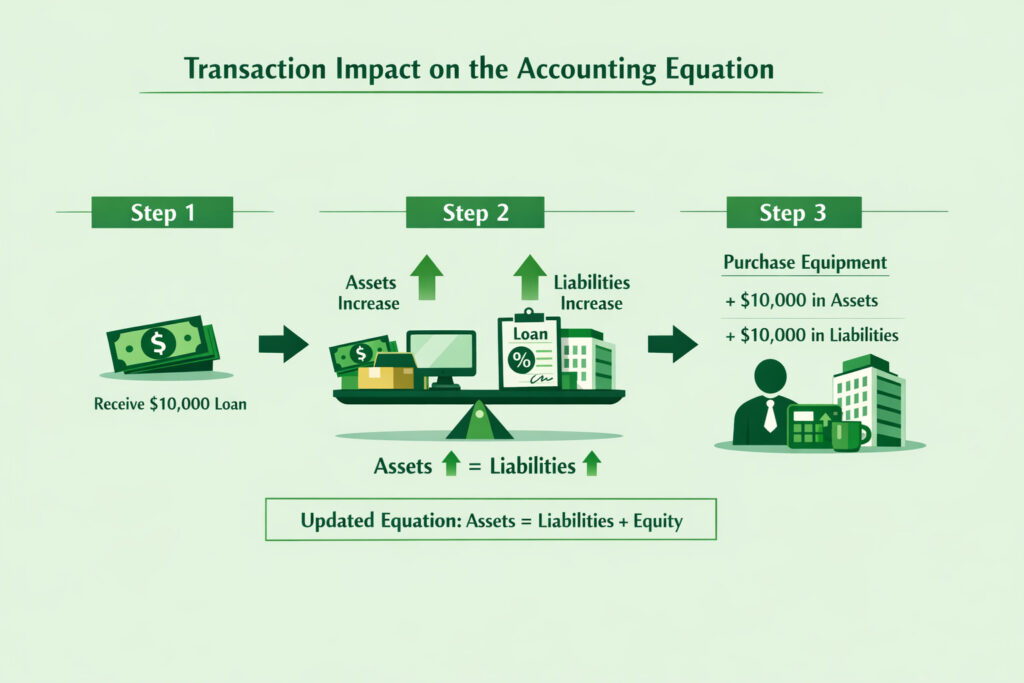

The accounting equation remains in balance because every transaction affects at least two accounts. This is the foundation of double-entry accounting. For example, when a business purchases inventory with cash, one asset (inventory) increases while another asset (cash) decreases. The total assets remain the same, and the equation stays balanced.

When a business takes out a loan, assets increase because cash is received, and liabilities increase because a loan is created. When the business earns revenue, assets increase through cash or receivables, and equity increases through retained earnings. When expenses are paid, assets decrease and equity decreases, reflecting reduced profitability.

This constant balancing ensures accuracy and consistency in financial records. If the equation does not balance, it signals an error in recording transactions. This makes the accounting equation not only a conceptual tool but also a practical control mechanism.

For non-accountants, understanding this logic demystifies accounting. Financial statements are no longer collections of unrelated numbers but structured representations of how assets are funded and owned. Once this relationship is understood, reading balance sheets and understanding business performance becomes far more intuitive.

Why the Accounting Equation Matters for Business Owners

The accounting equation is essential because it connects operations, financing, and ownership into one coherent framework. It helps business owners understand how daily decisions affect overall financial health. Buying assets, taking loans, earning profits, or paying expenses all influence the balance between assets, liabilities, and equity.

For decision-making, the equation provides clarity. It shows whether growth is driven by profits or debt, whether the business is overleveraged, and how much value has been built over time. It also supports better communication with accountants, lenders, and investors by providing a shared financial language.

Most importantly, the accounting equation turns accounting into a logical system rather than a mysterious one. Once business owners understand this equation, they gain confidence in interpreting financial statements, asking the right questions, and making informed decisions.

Conclusion

The accounting equation—Assets = Liabilities + Equity—is the backbone of accounting and financial reporting. While simple in appearance, it explains how every business is structured, funded, and owned. Assets show what the business controls, liabilities show what it owes, and equity shows what truly belongs to the owners.

By understanding this equation, business owners gain a powerful lens through which to view financial information. It transforms accounting from a technical requirement into a practical management tool. Whether running a small business or planning future growth, mastering the accounting equation is a crucial step toward financial clarity, control, and long-term success.